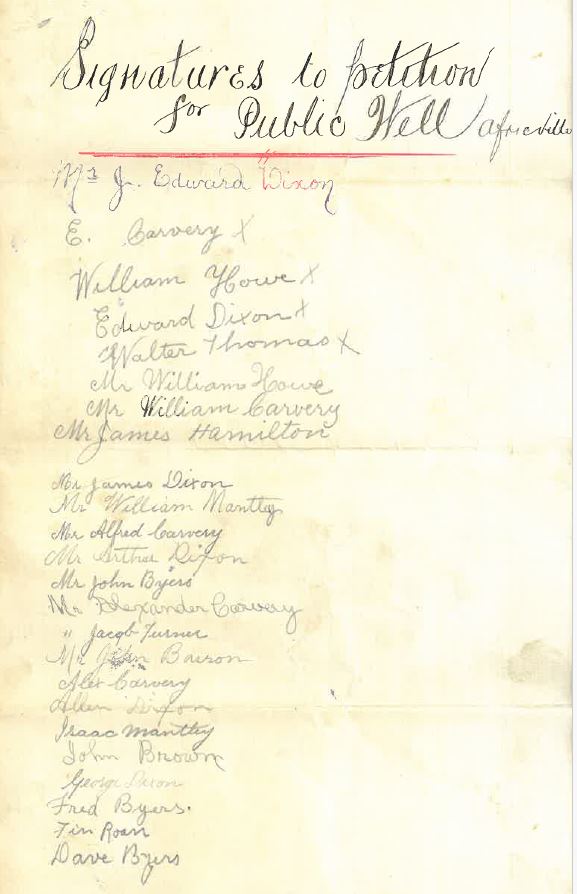

Being on Haligonian land, the residents of Africville were still considered citizens of Halifax, and therefore paid municipal taxes to the government. This relationship was one-way, however (McRae). The city repeatedly refused to provide the residents of Africville with infrastructure that would be considered essential anywhere else in the city, including clean water and sewage.

A water well in Africville with a sign reading "Please boil this water before drinking and cooking" ("Gone But Never Forgotten").

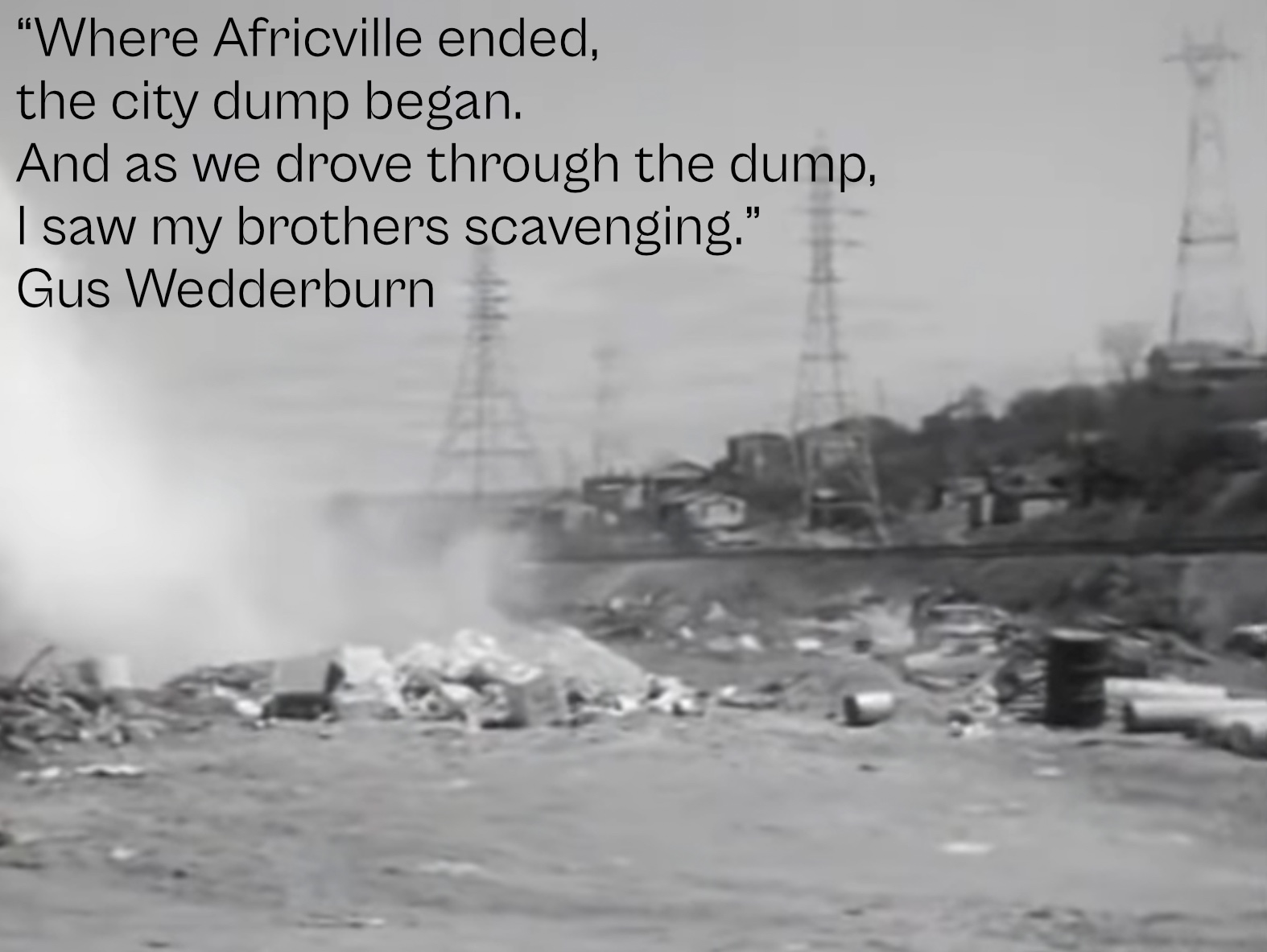

This culture of neglect from the city persisted throughout the entirety of Africville’s existence. In 1854, just 6 years after Brown and Arnold’s purchases of land, Halifax constructed a railway line right through Africville, running through houses in the process (Khan). In the decades following, the city greenlit many undesirable industrial projects around Africville, including a prison in 1859 (Edwards, “Rockhead Prison”), and an infectious disease hospital in 1870 (Edwards, “Infectious Disease Hospital”). This continued all the way up until the 1950 construction of a public dump mere meters away from Africville.

A photo of the city dump, with Africville visible behind clouds of dust (Remember Africville, 00:06:45).

The infamous Halifax Explosion of 1917 had destroyed buildings all across Halifax. Of the millions of dollars in public and private funds allocated towards rebuilding and revitalization of communities, Africville didn't get a single dollar (McRae). Whether the toxic smoke from the railway, or toxic groundwater polluted by the dump, the city of Halifax spent the better part of a century engaged in a willfully ignorant strategy of environmental racism, degrading the living conditions of the area to justify future displacement. Despite paying for the city's growth, Halifax completely ignored the large and established community that sat atop the land and treated it only as undesirable soil.